You are probably getting brain damage from all those COVID infections.

A worrying look into the literature on COVID and brain health.

It has been half a decade since the COVID-19 virus burned over the world, leaving millions dead or disabled, and forever changing the landscape of modern life. While the days of lockdowns, mask mandates, and weekly testing are long behind us, the COVID virus itself hasn’t gone away; it continues to circulate, mutate, and spreads through communities – still infecting thousands of people per day. Now that we have moved past the era where the most concerning outcome of COVID was death, it’s worth asking: what are all those COVID infections doing to us?

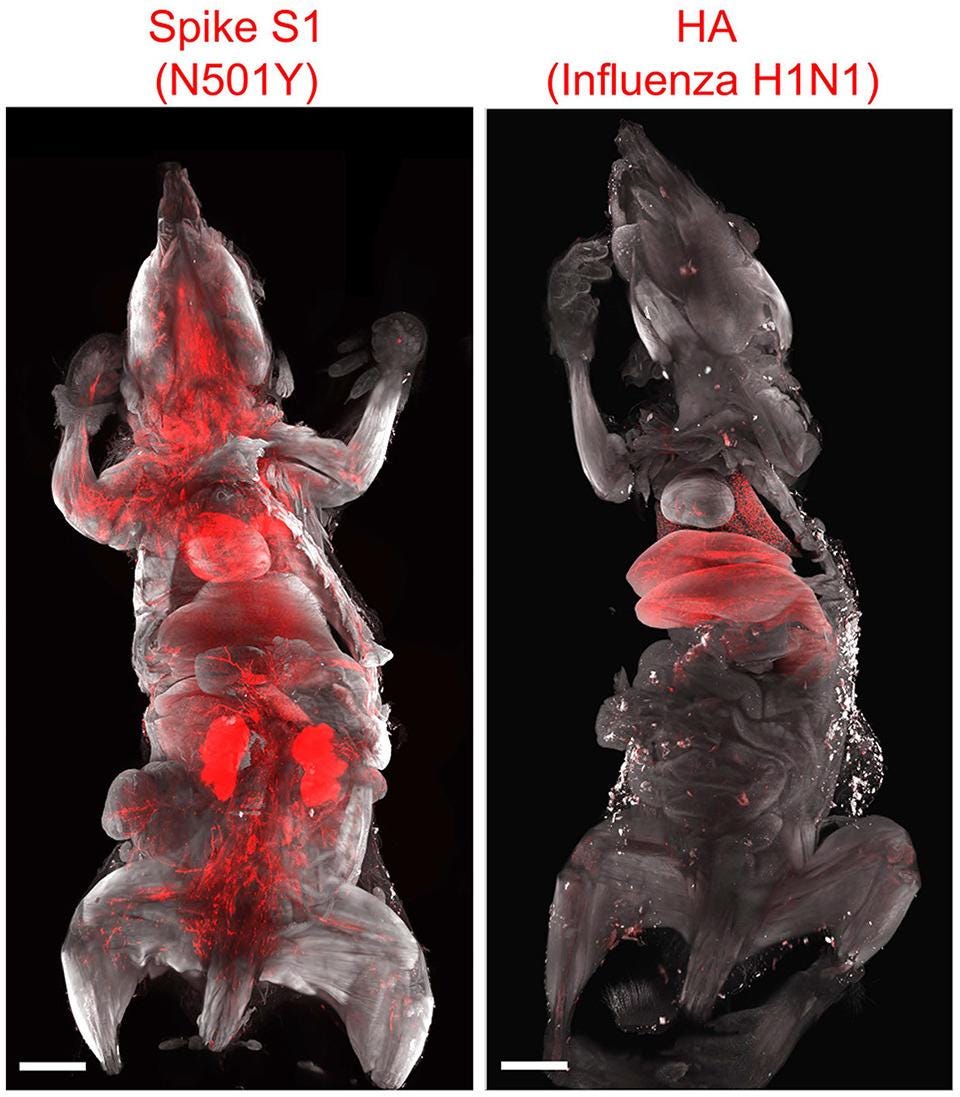

Despite popular perception, COVID is not “just a cold” – in fact, it’s not even really a cold-like or flu-like respiratory disease. Instead, the COVID virus is able to widely disseminate itself throughout the body, impacting organs that the flu never touches (see the figure below).

While the flu remains largely restricted to the respiratory system, COVID gets everywhere. Including that most critical of systems: the central nervous system. The virus can infiltrate the brain and meninges persisting there long after the acute infection is over (much like herpes viruses that also linger the nervous system for decades and reemerge to cause shingles later in life). Exactly how the virus gets into the brain is unclear, although it may travel along the olfactory nerve, effectively bypassing the protections that the blood-brain barrier usually provides. Once in the delicate network of the nervous system, the virus can trigger neuroinflammation, driving the immune system crazy and potentially leading to widespread damage.

COVID changes brain structure...and can cost you IQ points

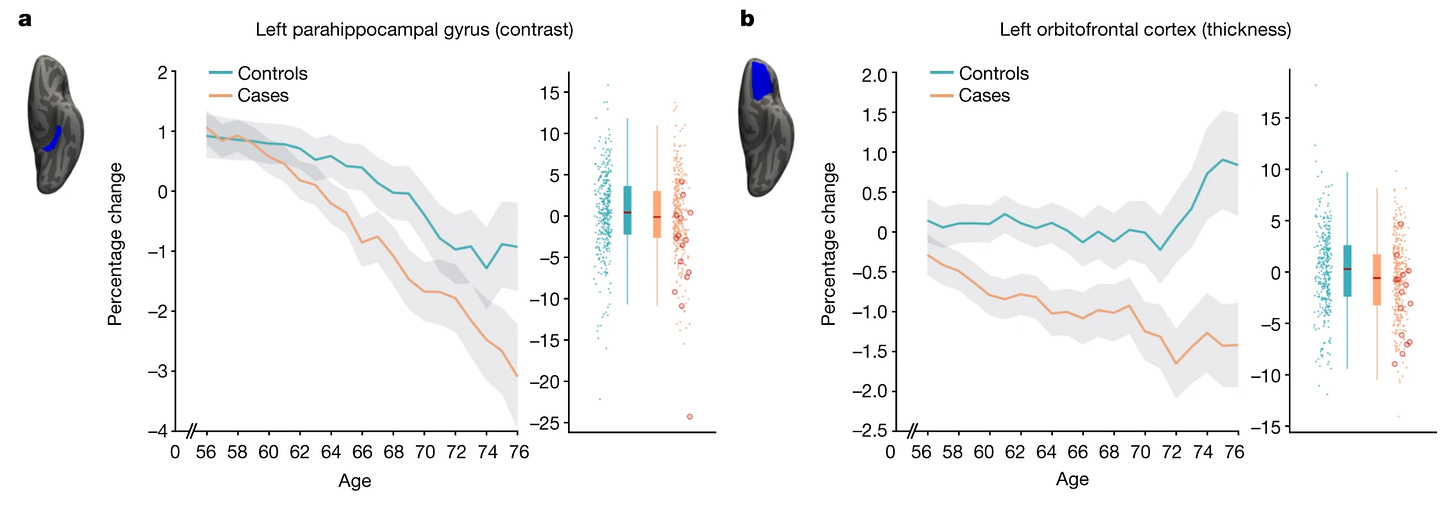

The idea that COVID could damage the brain appeared very early in the pandemic. In 2022, a longitudinal UK Biobank study found striking evidence infections impacted the brain. By comparing brain scans and behavioral measures done before the pandemic with repeat scans done after the emergence of COVID, scientists could directly test whether those who had contracted COVID in the interim differed over time from those who didn’t. They found that infections were associated with decreased gray matter thickness is two key brain areas: the orbitofrontal cortex (part of the prefrontal cortex involved in executive function and decision-making) and the parahippocampal gyrus (important in memory, spatial navigation, and emotional processing), and a global reduction in brain size. COVID was literally shrinking brains. Infection was also associated with impaired cognitive performance as well: over time, individuals who had contracted COVID showed degraded performance compared to those who hadn’t gotten sick. Importantly, these results held up, even when controlling for severity: even in people with “mild” COVID (i.e. those that didn’t require hospitalization), the pattern was consistent.

Around the same time, studies began to appear suggesting that apparently “recovered” COVID patients still suffered from impaired cognition. A 2022 meta-analysis of twenty two studies found lingering impacts on executive function, attention, and short-term memory, although these were generally studies of individuals who had been hospitalized (which is how they got on scientists radar).

Published just two years into the pandemic, these studies were the first, worrying signs that the COVID-19 virus was not just a respiratory issue, and that the damage it did could cut much deeper and injure us in far more profound ways. Newer studies still suggest that COVID is bad for our minds and brains. A 2024 study of ~112,000 people taking cognitive tests found that even short, mild COVID infections were associated with small, but measurable, cognitive deficits after recovery (a loss of about 3 IQ points). Severe cases requiring intensive care were associated with much steeper deficits (corresponding to a loss of -9 IQ points). Before anyone says “well, no one is hospitalized for COVID anymore”, the CDC predicts that, the week I write this, 10,300 weekly hospital admissions for the disease. Collectively, that’s a lot of IQ points that may go up in smoke. These results are consistent with another 2024 study, which compared patients who recovered from mild, moderate, and severe COVID found that all three groups showed statistically significant cognitive difficulties after recovering: even in the mild group, 11% of participants showed deficits in at least one area of function 1.5 years after their infection.

Collectively, these results suggest that even mild COVID infections may leave their mark on your brain, robbing you of IQ points, and making you that much worse at cognitively intensive or demanding tasks.

Infants and COVID

One area of particular concern is whether infants and children, whose brains are still developing, may be impacted by infections. There is ample evidence that prenatal and perinatal exposure to viral infections can have adverse developmental effects on babies (most famously, the Zika virus can cause microcephaly and other birth defects). While most neurodevelopmental disorders are thought to be largely genetic in origin, maternal fevers and inflammation during pregnancy are recognized risks of autism, ADHD, and developmental delays. It is certainly plausible that early-life exposure to COVID might be problematic, but unfortunately, the virus itself hasn’t really existed long enough to get a sense of what the impact on development might be. The earliest possible COVID-babies are just now turning 5.

The literature that does exist, focusing on the first months and years of life conflicted with some studies showing no effect, and some showing worrying effects. In one heartening study, a clinical trial that tracked pregnancy outcomes of 217 maternal COVID cases found no significant link between maternal COVID infection and developmental delays in the first two years of life. A 2022 study found that being born during the pandemic did predict neurodevelopmental difficulties at six months, but there was no significant effect of maternal COVID exposure, suggesting that the drivers were social and environmental, as did a more recent study looking at differences at six and twelve months.

Conversely, a study of 867 infants exposed to COVID in utero found an increased risk of receiving any kind of neurodevelopmental diagnosis by age three – although curiously, this was mostly in male children. A very recently published study recruited 124 mother/infant dyads early in the pandemic and tracked developmental outcomes for babies who had been exposed to COVID in utero compared to control. They found that exposure was associated with decreased cognitive and social skills in toddlers at two years of age, and that these effects were mediated by measurable changes in physical brain structure. Animal models of prenatal COVID exposure have found evidence of changes in brain composition and behavior, although there are obvious issues with drawing links between animals in humans when it comes to questions of brain and mind.

Beyond prenatal exposure, there is also the question of what the impacts of the COVID virus in infancy or childhood might be. A prospective study of 20 neonates found that those that contracted COVID during the first wave had increased risk of developmental delays in expressive language, fine motor control, and receptive language skills at 18-24 months of age (although the severity was generally mild). An ongoing study of 541 children who had ever had a COVID infection found that they were more likely to report more severe pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep issues compared to non-infected controls.

Clearly, deep uncertainties remain on what the long-term impacts of circulating COVID will mean for the neurological health of our children. It will take years for the first generation of COVID babies to mature, and there will always be the confound of what differences (if indeed there are any) are attributable to the biological impacts of infection versus the socio-cultural impacts of the pandemic. There is certainly reason to be concerned, though, and the existence of charities like Long COVID Kids (which advocates on behalf of children and families stricken by post-COVID syndrome) makes it unambiguously clear that the optimistic early-pandemic era claims that “kids don’t get COVID” or “kids don’t get Long COVID” were laughably false.

COVID as a risk-factor for dementia

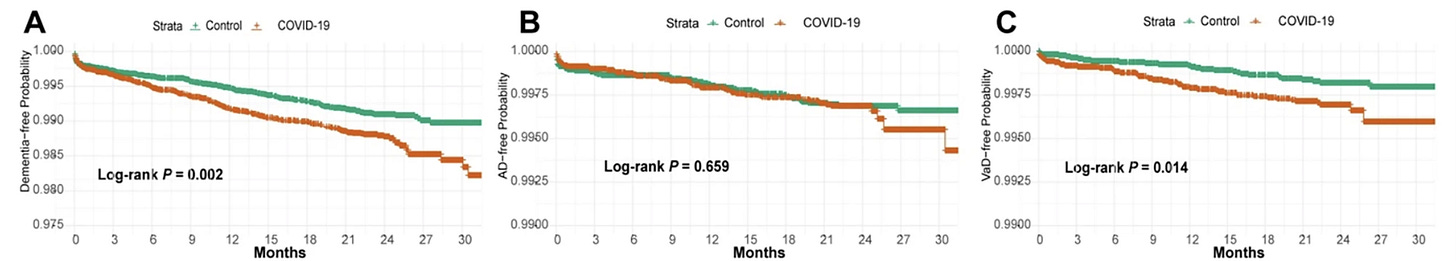

On the other end of the human lifespan are the effects of COVID on brain health in old age. Unlike with children, it is becoming unambiguously clear that COVID can be a potent accelerator of dementia and neurodegeneration. A massive analysis of clinical data from the Department of Veterans Affairs, published in Nature Medicine, found that the risk of a huge number of neurological issues spiked after an acute COVID infeciton, including stroke, cognition and memory disorders, peripheral nervous system disorders, migraines, seizures, mental health issues, and more. Narrowing in on dementia specifically, a Chinese meta-analysis of 15 retrospective cohort studies found an increased risk of dementia that persisted for at least two years after the acute phase of the infection. This is a well-replicated finding: another analysis, also from China, of a million post-COVID survivors and over six million controls found that the rates of new-onset dementia were ~1.82% in the survivors group, but only 0.35% in the control group. In the UK Biobank, an analysis of 50,000 individuals found that COVID infection was associated with a 58% increased risk of all-cause dementia. Interestingly, the effect was driven primarily by vascular dementia (rather than Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s), which makes sense given that COVID is widely understood to be a vascular disease.

And the bad news keeps coming. A 2024 meta-analysis of 18 studies and a total population of 412,957 COVID survivors (and 411,929 controls) found that, for individuals over the age of 65, as many as 65% of adults showed new-onset signs of cognitive impairment following recovery from acute COVID.

The idea that a virus, even a transient, generally “mild” one, might trigger neurodegeneration later in life is not particularly unusual – in fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that many neurodegenerative disorders may be post-viral in nature. In that light, it is hardly surprising that COVID would as well, although unlike many other viruses that you generally get once (e.g. EBV, chicken pox), we don’t build permanent immunity to COVID. We just keep getting it.

The problem of repeated infections

This, more than anything else, is what makes COVID unusual compared to the other viruses thought to cause brain issues. It is everywhere, and we keep getting it. COVID doesn’t lead to permanent immunity – and the transient immunity you do develop (either after infection or vaccination) wanes after just a couple of months. In 2026, it’s almost impossible to estimate how many times the average American has had COVID – people don’t test anymore and the tests themselves have a high false-negative rate. If we conservatively assume about one infection per year, a lot of people are going on close to half a dozen infections.

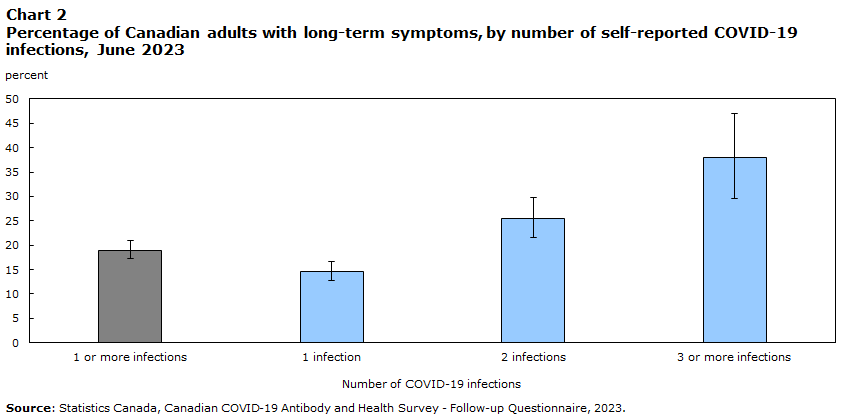

What do we know about repeated infections? The data, perhaps unsurprisingly, doesn’t look great. The NEJM study I mentioned above (the one that estimated a loss of 3 IQ points following first infection compared to COVID-naive controls) also estimated that reinfection cost another 2 IQ points on top of what was already lost. A study of children and adolescents (who are repeatedly exposed through school environments) found that reinfection was associated with a 2x greater risk of fatigue, pain, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, mental health issues, and cognitive dysfunction. This is consistent across large cohort studies: a large study of healthcare records from Singapore found that reinfection was associated with a 21% increased risk of post-acute symptoms, including psychiatric and neurological issues. Finally, it appears that the risks of reinfection compound with the number of cases: a study of VA records found that people with three or more infections had worse outcomes than people with zero, one, or two infections, with the burden increasing with number of infections. An analysis by StatsCanada found the same pattern: by three or more infections, the number of adults reporting at least one long-term symptom was approaching 50%.

A child born in 2026 could conceivably have as many as 10-20 COVID infections by the time they reach adulthood (assuming a conservative rate of one infection every 1-2 years, mostly through school exposure). They will have received repeated insults to their immune system, their nervous system, and their circulatory system, in every major developmental period, from early life, through puberty, and into early adulthood. It will take us decades to see what the consequences of this will actually be at the individual or societal level, but this is something we need to start taking seriously now.

Reflecting on the path forward

So where does this leave us in 2026? Having read well over a hundred pages over dozens of studies to research this, I have to say, the situation doesn’t look great. If I am being honest, my greatest hope is that this is all just wrong – that some combination of perverse publication incentives, negativity bias, and plain bad luck have all conspired to create a sort of scientific hallucination, a literature built on a nonexistent phenomenon. Perhaps in 15 years nothing will have actually changed and I’ll look back on this Substack as nothing more than an exercise in cringe. It would be nice if that happened, but it doesn’t seem likely. The COVID-causes-brain-damage hypothesis combines mechanistic plausibility (infiltration of the nervous system and inflammatory actions) and is backed up by both in vivo animal studies (see the poor mice above), and population-level public health data. This isn’t some bro-science sales pitches, where someone trying to sell you a supplement points to a study of just eight rats. Multiple lines of evidence, at multiple causal scales, are converging on this idea.

If we can’t hope that this has all been a big misunderstanding, then the next option would be a techno-fix. Scientists are finally beginning to untangle the mysteries of the neuro-immune interface and recognizing its importance for health, longevity, and mental wellness. Perhaps there is some magic drug, supplement, or other medical miracle waiting to be discovered that will solve this problem for us. Maybe we just have to ask some future generation of Claude Opus to solve it for us. Maybe. But as the US turns its back on scientific funding and Americas’ research institutions begin to crumble, I’m feeling less optimistic that science will come to our aid. I had (perhaps naively) thought that the COVID vaccine would prove to be a “Sputnik moment”: that a country rescued from the jaws of Hell by the heroic work of biomedical scientists would enthusiastically invest in pushing the horizons of knowledge forward. Instead we got anti-vaccine lunatics and the triumph of RFK Jr.-style medical misinformation. Rather than boldly pushing forward, we seem to be turning in on ourselves, cannibalizing what we have and turning to strange superstitions and conspiracy theories. The United States is not the only country on Earth, of course – breakthrough science could come out of Europe, or China, or anywhere else. Unfortunately, around the world national priorities are shifting towards defense as the post-WWII order fragments and it feels like the era of transnational, interdisciplinary blue-sky scientific research that defined the last fifty years is coming to a close. Perhaps some billionaire oligarch will get Long COVID and that will inspire him to pour money into, but short of that, now does not feel like a great time to be betting on science to solve our problems.

At the individual level, the best advice is probably “don’t get COVID”, although this is almost impossible to do totally at this point, unless you live essentially in lockdown (which is neither desirable, nor financially tenable for most people). Getting vaccinated and masking certainly help minimize individual risk, but with vaccination rates cratering, the population-level effects of COVID seem well and truly locked in at this point. Whatever COVID does to human brains, it’s going to do it to a lot of them. Repeatedly. Forever.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how much the world changed in my grandmother’s lifetime. She was born in Wisconsin, in a time when horse-drawn carriages were still a thing. She lived to see men walk on the moon, and by the end of her life, she had a PC in her bedroom and was sending emails to her friends from church. As a culture, we’ve grown used to the idea of change – after all, it defined the last century – but we have a kind of in-built optimism that the change will always be for the better. That the economy will grow and that every generation will live longer, healthier lives than the one before it. We’ve been lucky that, by and large, this was true for the last hundred years, but it doesn’t have to be true. Perhaps this is just a bad change. One was bound to happen sooner or later. We might just be entering a new era, perhaps analogous to the era of leaded-gasoline, where the population as a whole is just sicker, our brains are more inflamed, and we’re all just a little dumber than we might otherwise have been. I have no doubt that humanity will make it through as a species (we’re quite hard to kill, and we did learn to take the lead out of gasoline, eventually), but for now, it might be time to buckle up and get your helmet on, because it could be a very, very bumpy ride.

Key References

Al-Aly, Z., & Rosen, C. J. (2024). Long Covid and Impaired Cognition—More Evidence and More Work to Do. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(9), 858–860. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2400189

Bowe, B., Xie, Y., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nature Medicine, 28(11), 2398–2405. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02051-3

de Pádua Serafim, A., et al. (2024). Cognitive performance of post-covid patients in mild, moderate, and severe clinical situations. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01740-7

Douaud, G., et. al. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature, 604(7907), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5

Goyal, M., et al. (2024). Long-Term Growth and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Neonates Infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 Pandemic at 18-24 Months Corrected Age: A Prospective Observational Study. Neonatology, 121(4), 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1159/000537803

Hampshire, A., et. al. (2024). Cognition and Memory after Covid-19 in a Large Community Sample. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(9), 806–818. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2311330

Jaswa, E. G., et. al. (2024). In Utero Exposure to Maternal COVID-19 and Offspring Neurodevelopment Through Age 24 Months. JAMA Network Open, 7(10), e2439792. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.39792

Kuang, S. (2023). Experiences of Canadians with Long-term Symptoms Following COVID-19. Statistique Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00015-eng.pdf

Lim, J. T. et. al. (2025). Multi-systemic risk of post-acute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. BMC Global and Public Health, 3, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44263-025-00222-1

Montealegre Sanchez, G. A., et. al. (2025). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 long term outcomes study (PECOS): Cross sectional analysis at baseline. Pediatric Research, 98(2), 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03777-1

Rong, Z. et. al. (2024). Persistence of spike protein at the skull-meninges-brain axis may contribute to the neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Cell Host & Microbe, 32(12), 2112-2130.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2024.11.007

Shan, D., et. al. (2024). Temporal association between COVID-19 infection and subsequent new-onset dementia in older adults (aged 60 years and above): A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 404, S73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01987-1

Shan, D., et. al. (2025). COVID-19 infection associated with increased risk of new-onset vascular dementia in adults ≥50 years. Npj Dementia, 1(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44400-025-00034-y

Shuffrey, L. C., et. al. (2022). Association of Birth During the COVID-19 Pandemic With Neurodevelopmental Status at 6 Months in Infants With and Without In Utero Exposure to Maternal SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(6), e215563. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5563

Shook, L. L., et. al. (2026). Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of 3-Year-Old Children Exposed to Maternal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Utero. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 147(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000006112

Shrestha, A., et. al. (2024). The risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults diagnosed with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 101, 102448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102448

Tavares-Júnior, J. W. L., et. al. (2022). COVID-19 associated cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Cortex, 152, 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2022.04.006

Thomason, M. E., et. al. (2025). COVID-19 infection during pregnancy and infant neurodevelopment. Pediatric Research, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04409-y

Vanderheiden, A., & Klein, R. S. (2022). Neuroinflammation and COVID-19. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 76, 102608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2022.102608

Weiner, S., et. al. (2026). The COVID generation: The neurodevelopmental consequences of in-utero COVID-19 exposure. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 133, 106238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2025.106238

Xu, E., Xie, Y., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 28(11), 2406–2415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02001-z

Zhang, B., et. al. (2025). Long COVID associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection among children and adolescents in the omicron era (RECOVER-EHR): A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00476-1

Zhang, Q., et. al. (2025). Risk of new-onset dementia following COVID-19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing, 54(3), afaf046. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaf046

There's entire internet communities full of people who wear N95 or FFP3 respirator masks to avoid catching covid. Check out reddit.com/r/ZeroCovidCommunity

Some people on there are healthcare workers, teachers, service staff or others who work with the public. Through a combination of masking and ventilation many of them have avoided catching covid. It's possible. Of course it often harms you social life but so do getting long covid.

A recent study has suggested that COVID-19 infections might also trigger an increase in mental health issues like depression and anxiety, not only cognitive decline. These psychological effects could persist long after recovery. In my opinion, the mental health ramifications might be just as concerning as the cognitive ones, possibly leading to a hidden societal crisis.